Why Is Medical Screening Important?

Many expedition team members, leaders and medics will have past or current medical conditions, injuries or disabilities. With more and more people undertaking mountain adventures and the average age of these people increasing, it follows that more people will be managing chronic (long term) medical conditions. For most people this shouldn’t stop them going on an expedition or from having a brilliant time and achieving their expedition goals. However it is important to understand that many medical conditions can be exacerbated by the environmental extremes of an expedition e.g. high altitude and cold temperatures, and by the other changes during an expedition that impact on our physiology and mental health e.g. poor sleep, change in diet, psychological and physical stress.

For people with pre-existing conditions, a good expedition medic adds value before the trip by screening all expedition team members. Using information gained from this process they can create and discuss a pre-trip medical and fitness optimisation plan with individuals, give appropriate advice on self-care to prevent deterioration of conditions before and during the expedition, and make contingency plans for medical problems that may occur during the expedition.

Good medical screening, well before the expedition allows for adequate planning of everything from what to put in the medical kit to planning how to detect and mange specific condition related complications e.g. ensuring a good supply of emergency drugs and kit to manage seizures if a group member is known to have epilepsy. We all know that prevention is better than cure and in remote and often hostile environments, this is even more crucial. Prior knowledge allows us to reduce the risk of problems occurring by making plans to aid prevention or help intervene early before conditions deteriorate further.

This doesn’t just hold true for people with current conditions but is also important for people with relevant past medical problems. An expedition specific example is someone who has suffered from altitude illness on previous ascent to high altitude (more than the common mild, self-limiting symptoms). There is evidence that previous altitude illness is a risk factor for developing it again on future ascents. Depending on the circumstances of the prior bad experience, it may be appropriate to alter plans to help prevent future problems at high altitude e.g. spend more time acclimatising and/or reduce the maximum altitude target of the expedition or just for that person.

I’ve had several cases where I was particularly grateful for detailed medical screening. One that springs to mind was a woman in her early sixties who declared on her medical form that she only had one kidney, a history of mild renal impairment and hypertension (high blood pressure) currently controlled by two anti-hypertensive medications. She was planning a challenging high altitude expedition and amongst other questions, she asked whether I would advise her to take Acetazolamide (Diamox) to help her acclimatise. Given her vulnerable single kidney, the risks of potential renal damage involved with a high altitude trek (e.g. dehydration secondary to GI upset or acute mountain sickness (AMS)) mixed with her current medication, the decision to use Acetazolamide was too specialised for me to competently answer. Due to timely pre-expedition screening, this woman was able to get blood tests to check current renal function and I had time to consult a friend who is a Consultant Renal Physician and experienced mountaineer, for some advice. Between the three of us we were able to come up with a personalised plan that we were all comfortable with, not only in case things went wrong, but also to optimise this woman’s chances of expedition health and success. She did successfully complete the expedition with no issues except some mild AMS.

Exclusion on Medical Grounds

Some expedition members are concerned that the medical screening will result in them being excluded from the expedition. For a very small minority of people this is true; where the risks of an expedition causing serious illness or even death due to a deterioration in their pre-existing health condition are considered too high. This depends on a huge number of factors and the decision is never taken lightly. Considerations include the specific medical condition, the person’s understanding of their condition, their current condition management and stability of the condition, the expedition location, length, resources and the in-country facilities. It also vital to consider the rest of the group and the levels of risk that everyone feels they can accept. The physical and emotional challenge of most expeditions may lead to deterioration in the person’s underlying condition and if this were to happen to a severe extent, the facilities available on expedition may not be adequate to cope with the nature of the problem.

Here are a few examples of situations where pre-existing conditions would pose an unacceptable level of risk on a remote expedition. Every case is different but it hopefully gives you some idea of the reasoning expedition medics use; it’s not necessarily the condition itself that causes the most concern, but how stable or unstable the condition may be for that particular person:

- A person with newly diagnosed Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) who is still getting used to their condition, managing their blood sugars, injecting insulin etc. is not someone I would feel comfortable taking on an remote expedition with no means of rapid evacuation to high class medical care. Amongst other problems, without tight blood sugar control, T1DM can rapidly cause life-threatening complications if the blood sugar falls very low (hypoglycaemia) or becomes too high leading to diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). These conditions need urgent, specialist medical help. For someone newly diagnosed with T1DM, their understanding of their condition and how it effects them daily is still likely to be low and they are probably not yet confident managing their condition in their normal dad-to-day life. Expeditions usually include long journeys affecting sleep cycles, physical exertion and often dramatic changes in diet. All of these factors play havoc with diabetes control so the person needs to be completely confident and competent to manage their condition without help before travelling. Clearly someone with longer standing, well controlled diabetes is a very different kettle of fish and with good planning, diabetes should not stop them undertaking their adventure.

For more information on travel with diabetes see the Oxford Handbook of Expedition and Wilderness Medicine and UIAA website and this paper: https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/pdf/10.1089/ham.2018.0043

- People with a severe and recently unstable mental illness won’t be suitable for a remote expedition. Severe, chronic mental illnesses such as schizophrenia, bipolar affective disorder or severe on-going depression will need at least a significant period of stability before the person should be considered for an expedition team. This is highly individual and there are many factors to consider but as the expedition doctor, you have to think about how you would manage the person effectively, as well as the rest of the group, if they became severely mentally unwell on an expedition. You will need to keep the person safe and get them to specialist psychiatric care, which may not be easy or even possible in certain areas of the world. This is not to say that people with chronic mental health problems should be excluded from expeditions, but as with physical health issues, their condition needs to be stable, well understood by the individual, well-managed and at low risk of sudden deterioration before travel to remote places is considered.

- Pregnancy – I would not accept anyone who is pregnant as a member of an expedition. The risk of problems is high in early pregnancy and the reality of remote expeditions is that immediate evacuation usually isn’t possible. Even whilst trekking in the Khumbu region of Nepal, where helicopters are seen regularly, you can’t always get one when you want one e.g. overnight or during bad weather. Consider the risks of early pregnancy related complications – imagine having to manage a rapidly deteriorating patient with an ectopic pregnancy, or trying to medically and emotionally manage someone having a miscarriage and then being told you have to wait a day or two for evacuation… need I say more?

The Pre-Expedition Medical Questionnaire

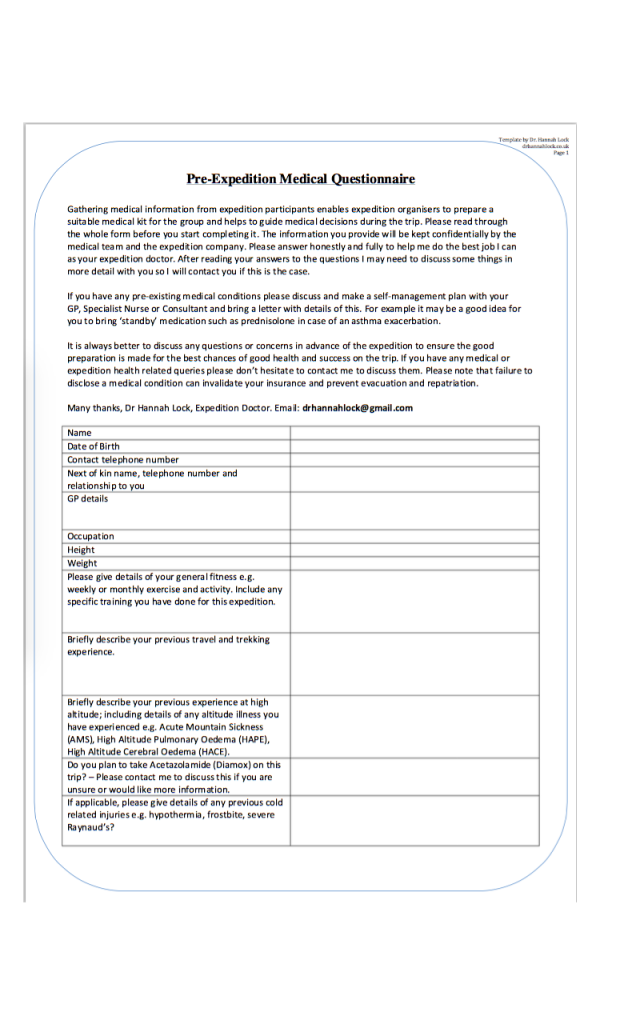

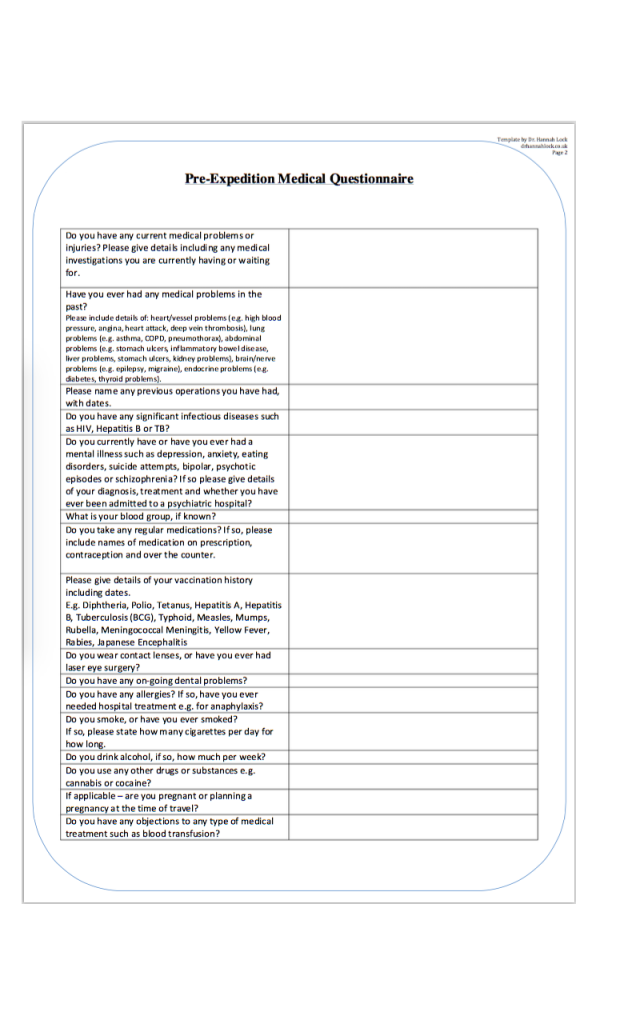

Several months before any expedition, I email the group to introduce myself, tell them a bit about myself and ask them to complete a pre-expedition medical questionnaire. I then do a follow-up telephone call with group members once I have received and read their information. Following this, for some people with certain conditions I may ask for more information or ask them to book a review with their GP, Specialist Nurse or Consultant.

I don’t rely on any company or other organisation to send their own questionnaire unless I’ve seen it first and feel comfortable with the level of detail it includes. If you are the responsible doctor or medic, you need to be happy with the information you are working with.

Here is the questionnaire I have designed and use for high altitude expeditions:

Non-disclosure

Non-disclosure is always a potential issue, not only with group members but with expedition staff members too. It is very difficult to ensure people disclose all their medical information but hopefully by being friendly and open about why you want the information and how you can help, the vast majority of people will be honest. It is also important to remind everyone that failure to disclose a medical condition can invalidate their insurance and prevent evacuation and repatriation.

In Summary…

As the expedition doctor or medic, you can only adequately plan for your role by knowing the relevant information about your group first. It’s not just planning to prevent or manage emergencies that is important – I strongly believe that a personalised plan to help individuals optimise their health and pre-existing conditions is one of the best ways to ensure they have the most fun and success on their expedition because hopefully their health won’t cause them any unexpected issues and if it does then they have a plan of how to deal with it.

It is also important to ask for help or advice from other mountain medics if you come across a condition or situation you’re not sure about how best to manage before or during an expedition. There is an amazing community within the British Mountain Medicine Society and they are a great source of advice and information. One of the membership benefits of joining the society is access to a large email group of medics from all over the UK (and some from further afield), all with a special interest and experience in mountain medicine.

I’ve found that the majority of people engage well with my screening questionnaire. I’ve had positive feedback about the process I use (emailing to introduce myself, the questionnaire, an expedition health advice sheet (not included in this article but will be a future blog post) and then a follow-up phone call). I’ve also been told people find it reassuring to get to know their expedition doctor well in advance of the trip. As with all branches of medicine – a good relationship with your patient is key to the success of any illness prevention plan or treatment plan. I think that building the foundations of this relationship before the expedition is vital.

Please feel free to use my screening questionnaire for your own expedition groups if you find it useful. You can download it by clicking the link in my resources page.

As always, I’d love to hear your thoughts so please feel free to comment or ask questions. Thank you!

Very informative, thank you.

Thanks, glad it’s useful.