Even the best-planned adventures can go completely off track when the weather changes, a rock falls or the snow pack doesn’t behave as expected. When accidents happen in the mountains, it is not only physical injury we should be concerned about as mountain medics and professionals, but psychological injury too. This article will briefly explain what stress injury is and talk about what we can do to manage this in our casualty, the wider group and in ourselves.

Stress Injury

Stress injury is a psychological response to a traumatic event. It is important to note that what constitutes a traumatic event is subjective, where some events e.g. a climber taking a large lead fall, sustaining multiple injuries would be classed as a traumatic event by most people, some people may still be deeply psychologically affected by significantly less extreme events that others may not be particularly worried by and didn’t require a rescue. We have to acknowledge that everyone responds differently and we need to support everyone in all events where something has gone wrong or an accident has happened in the mountains.

At the time of the traumatic event, the body releases stress hormones that can lead the brain to form detailed memories and create a highly emotive record of the event. Importantly, this stress injury can happen to people who don’t suffer the physical injury themselves but have witnessed the event. This is critical to remember as a mountain medic or leader because you are responsible for the health and safety of the whole group, not just the person with the physical injury.

For some people their traumatic experience is so overwhelming that they are left feeling as though they cannot move on, they feel on edge and unable to heal. Stress injury describes a spectrum of different responses. Without support, these feelings can lead to mental health problems such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), at the severe end of the spectrum. Providing psychological first aid to the victim as soon as possible may reduce the severity of the stress injury.

What is Psychological First Aid (PFA)?

PFA does not require professional training – anyone can offer it. Put simply, PFA is showing humanity by providing supportive and practical assistance to the person involved in the traumatic event. It attempts to assess their needs, listen to their concerns and help to address their basic needs (e.g. food, water shelter, hope). PFA provides comfort and calmness for a person in distress and aims to protect them from further stress injury.

5 Treatment Principles of PFA

- Safety– Making someone feel safe is fundamental and providing shelter is an excellent start (a group shelter, a hut or even the lee side of a boulder) or moving them to a safer place on the mountain (e.g. away from the cliff – you would likely do this anyway as part of your initial group management after an accident). By good leadership, bringing some order to an accident scene and explaining the threat reduction reinforces the feeling of safety.

- Calmness– When the rescuer is calm, the casualty will sense this and is more likely to reflect it. It is not easy to stay calm when you yourself have witnessed the traumatic event so one method to achieve this is it to take some slow, deep breaths. You can then use the same simple techniques to calm the injured person – “Lets take a breath, count to four and then slowly let it out”. Getting the casualty to turn their focus away from the danger is a good way to help establish calm.

- Self and Community Efficacy –Involving the casualty in their own rescue and giving them purpose (e.g. “Can you hold this rope, while I tie this off?”) helps them feel some control over the situation and reduces feelings of helplessness, which in turn helps them feel safer. Helplessness is a strong predictor of stress injury. This is particularly important when children are involved in an accident.

- Connection –Human connection is the most basic form of social support and probably the most important part of PFA. Just being present with someone, letting them know they aren’t alone is very powerful. Use their name, chat about their life (if they are comfortable to do so) – talking about loved ones, hobbies and pets all go a long way to fostering a strong connection.

- Hope –Explain simple facts to show hope e.g. “We are warm and dry in the tent and we’ve contacted the rescue team, so help is coming.” Continue to provide positive, hopeful comments regularly.

Don’t forget the witness…

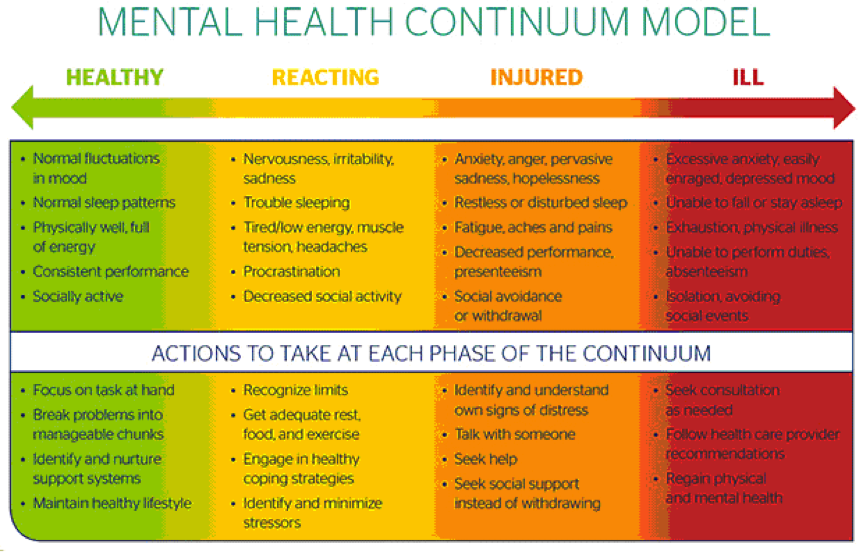

As mentioned earlier, stress injury can occur in people who have witnessed a traumatic event (rather than been the casualty) and this includes the rescuer/medic/team leader too. Remember to look after yourselves and acknowledge that you are human too and may need support following this event. Sometimes the stress injury isn’t apparent immediately but feelings can surprise you days or weeks later. The stress injury and response is a predictable and normal reaction to a traumatic event. The table below shows some of the feelings and behaviours you may display in the various stages of the stress response, in the medium and longer term following a traumatic event. Below each stage is a list of actions that may help you recover. The most important thing is to talk to someone about how you are feeling.

An excellent resource is this short film called ‘Resilience – The Avalanche’ made by my friend and fellow mountain medic Dr Matt Walton. I highly recommend you watch it. This film features a Mountain Rescue volunteer’s first experience of responding to a fatal avalanche and how he coped afterwards. He uses his experiences over 25 years of service to give advice on building personal resilience and staying well in the job.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qabCvFwmNyo

Matt’s first film, called ‘Resilience – One Team’s Trauma’ was produced by a helicopter emergency medical service team and provides an insight into the emotional responses experienced by the team after attending a critical incident and what has helped them to cope. Although this is not specifically mountain medicine, I still highly recommend watching this short film as there are some excellent learning points which are relatable for mountain professionals (leaders and medics) on dealing with traumatic events.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=5&v=DY60ZOWBvDc&feature=emb_logo

As always, comments and questions are welcome.

Interesting to read! I’ve just had a serious climbing accident with brain damage and a broken neck, back and hip. Lucky to be alive.

Si Lake

Hi Si, sorry I didn’t reply to you earlier, I’ve only just seen your comment for some reason! Wow that sounds extremely serious and life changing but definitely lucky to be alive, thanks for sharing it. I’m glad you found my article interesting. If you don’t mind sharing more about your accident and life since it, would you consider chatting to me at some point about it, potentially to make into a blog post interview? I completely understand if not, but if you’re happy to chat then please get in touch via email: drhannahlock@gmail.com. Thanks, Hannah